The Amazon is big. The Amazon is remote. The Amazon is unknowable. Or, at least, that’s what traditional science would tell us. The scale of the Amazon’s watershed is daunting (it’s about the size of contiguous United States), particularly when our goal is to answer questions using the scientific method, a method that depends on systematic and representative sampling to ensure that the study reflects the larger entity in question. Without a surplus of roads or airports to facilitate access into the Amazon, getting that representative sampling can be both a financial strain and a time drain for scientists–just picture the difficulty of creating camps in dense forest or carrying supplies on hard terrain in remote locations. But what if there were a way to achieve the necessary scale to answer scientific questions by involving others?

This is what citizen science proposes. While the Amazon might be big, remote, and hard to work in for small teams of trained scientists, the Amazon is not empty wilderness. It is filled with people who have local knowledge, and are capable of asking questions about their environment, collecting observations on it, and using that information to predict possible impacts and determine appropriate mitigation and monitoring methods. That’s where citizen science comes in.

Citizen science refers to the collective participation of non-specialists engaging in making observations and answering questions about the world. In the Amazon, engaging people to collect observations about natural phenomena or trends can be useful to both science and communities. It can generate comparable information at local and regional scales that would be prohibitively difficult for traditional science to achieve. This is not to say that citizen science is necessarily new in the Amazon. Conservation objectives and local cultural backgrounds have led to different types of citizen engagement models in this region.

There are plenty of examples of these models over time. One is among the longest running participatory monitoring projects in the floodplain forest of the Mamirauá and Amanã Sustainable Development Reserves. Local citizens realized that through monitoring, they could figure out ways to better the management of pirarucú (Arapaima gigas), an important food fish. Another model that has grown in popularity is volunteer tourism programs, in which tour agencies incorporate data collection or other volunteer activities into the trips they offer, which both acknowledges the lack of research funding and has the benefit of engaging new audiences in science and conservation. One successful experience of this model is the partnership between Rainforest Expeditions, the Tambopata Macaw Project, and the Earthwatch Institute in Peru, in which tourists experience the Amazon while helping monitor parrot populations. Environmental education also offers important opportunities for cementing environmental and scientific consciousness – in Ecuador, for example, the project Minga Para Mi Rio involves local school children around the San Pedro river to learn about aquatic ecosystems and then apply what they know in cleaning, restoring, and observing the river.

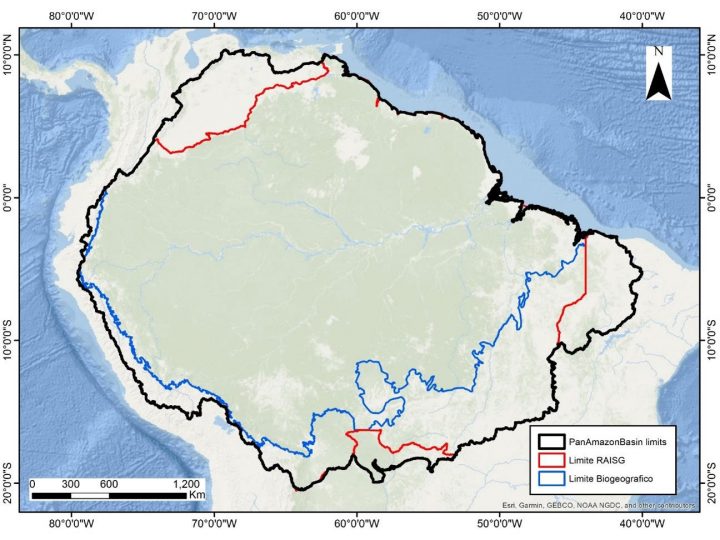

A newer project is the Citizen Science for the Amazon Project, which explores the increase scientific knowledge by crowd-sourcing data on fish sightings and water conditions in rivers throughout the Amazon basin. The project is creating a network of partner organizations and contributes to the goals of the Amazon Waters Initiative by improving our understanding of fish migrations and the environmental factors that affect them. By taking this approach, the project promotes the construction of an informed conservation constituency, and empowers citizens to take care of the Amazon basin, ensuring long-term engagement and conservation.

Recent advances in technology have created favorable opportunities to increase our knowledge of the Amazon, including its waters. More people can communicate and answer questions that can have impacts at both local and regional scales. For example, crowd-sourced data could be used to develop a management plan for a particular fishing area, inform a clean water policy from a local, regional, or national government, and make sure that you can keep eating your favorite fish in a sustainable manner. Or simply, it can remind you that while the Amazon is big, it is anything but unknowable.

References

Brightsmith, D. et al. 2008. Ecotourism, conservation biology, and volunteer tourism: A mutually beneficial triumvirate. Biological Conservation 141(11):2832-2842. DOI: 10.1016/j.biocon.2008.08.020

Citizen Science for the Amazon Project. 2017. 1st Partners Meeting Report. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0ByFivCQURRYrRkRyNWNoX0FrUms/view?usp=sharing

Eitzel, M. V. et al. 2017. Citizen Science Terminology Matters: Exploring Key Terms. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 2(1):1–20. DOI:10.5334/cstp.96

Minga Para Mi Rio. Canal Comunidad. https://www.ivoox.com/minga-para-mi-rio-audios-mp3_rf_848230_1.html

Painter, M., et al. 2008. Landscape Conservation in the Amazon Region: Progress and Lessons, WCS Working Paper No. 34. Bozeman: Wildlife Conservation Society.

Written by Natalia Piland.