Warning: Undefined variable $sitepress in /home/qq74lwf0j67d/public_html/wp-content/themes/atelier/includes/plugins/aq_resizer-1x.php on line 63

Fotografía: Walter Wust, WCS.

To Protect the Most Species, Plan for Freshwater Conservation

Integrated terrestrial-freshwater planning can support conservation of both ecosystems, say Cecilia Leal and colleagues.

A recent study comparing conservation scenarios in two locations of the Brazilian Amazon (Paragominas and Santarém) showed that by prioritizing both freshwater and terrestrial conservation, protected areas can increase freshwater benefits by up to 600% with a negligible 1% loss in terrestrial benefits. This is important because many current conservation strategies don’t take into account freshwater considerations. Justification is that there is little data about freshwater species, and that we can assume spatial overlap between terrestrial and aquatic species. Yet, this spatial overlap is often assessed at: a coarse spatial resolution, and it disappears when you zoom in; for a few taxonomic groups, and it’s not true for others; and without taking into account connectivity, which is vitally important for freshwater species.

Fotografía: Walter Wust, WCS.

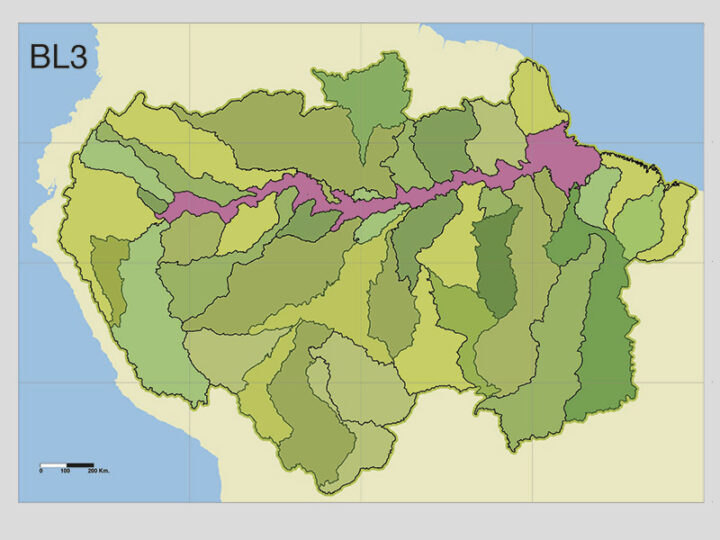

To get these results, the researchers went to many sites in these two locations and took data on common terrestrial and freshwater species groups that are used for conservation priorities (plants, birds, and dung beetles for the former; fish, dragonflies and damselflies, mayflies, stoneflies, and caddisflies for the latter). Then, they took that data and created distribution models, prioritizing different river catchments based on how diverse they were in each group (so, for example, a catchment with many bird species would receive a high priority score). Using those maps, the researchers pretended they had either a limited budget or a limited area they could conserve, and then made decisions of where to conserve based on freshwater or terrestrial species groups, and saw how it affected the others. This is how they realized that conserving by terrestrial groups was not a great way to conserve important areas for freshwater groups, but vice versa did a good job of covering both. If there’s not a lot of information on the freshwater groups, they also saw that planning for terrestrial groups with an element of aquatic connectivity did better than terrestrial groups alone.

This research shows us that conserving places with a freshwater lens does a better job of conserving both types of ecosystems than conserving them with a terrestrial lens, which is the more common practice. This is also likely to be conservative — freshwater ecosystems are so important to humans, beyond the species that live in them. For example, they provide water to drink, water for agriculture, water for rain, and water to navigate boats on from place to place. They are also places where people create social connections and maintain a spiritual connection to place. The fish species, too, contribute towards proper nutrition, which is not always taken into account in these types of scenario building. Conserving freshwater ecosystems and aquatic connectivity would support all of these! Leal and colleagues end their paper saying, “identifying promising new approaches for biodiversity conservation is only the first step toward improving conservation outcomes.” These approaches must also be converted into tangible benefits.

Fotografía: Walter Wust, WCS.

One way that these approaches can turn into tangible benefits is using data from many places to make models more specific and have interdisciplinary teams look for synergies. For example, researchers from many disciplinary backgrounds and multiple organizations are currently working on identifying how to best conserve freshwater elements in the Amazon. This team, led by the Wildlife Conservation Society and Florida International University, is looking at what variables we have to think about to support fish and fisheries, wetlands, and freshwater connectivity. By integrating and looking at the system holistically, the work will build upon Leal and colleagues’ work, providing a framework and proposal of indicators to monitor for conservation practitioners. Stay tuned!

Writted by Natalia Piland.